Has any one ever pinched into its pilulous smallness the cobweb of pre-matrimonial acquaintanceship?

This line is one iteration in the series of web metaphors in George Eliot’s Middlemarch. The web between people, of their feelings and relationships, is large and strong, but sometimes almost invisible in its gossamer threads.

The context here is that Dorothea knows very little about her suitor, but each crumb of information she gets expands in her mind, and the gaps in the image are easily filled in and embellished. Where she sees defects, she can use as an excuse her impartial knowledge, and hope that anything that appears lacking in him is due to her only having yet to discover it: “She filled up all blanks with unmanifested perfections, interpreting him as she interpreted the works of Providence, and accounting for seeming discords by her own deafness to the higher harmonies. And there are many blanks left in the weeks of courtship, which a loving faith fills with happy assurance.”

Thus with only a few meetings and the hearsay of others, Dorothea has a luminous image in her mind of Mr. Casaubon. Even more so, she has a luminous image of what their life together could be like, and how she will bloom into a better version of herself at his side. If one were to grab this web of impressions which expands across her whole vision, however, and press the fibers together into a little ball, it would be no larger than a pill: hence, the “pilulous smallness.” As the sentence which precedes the quote I chose mentions, though, this illusion is not a sign of Dorothea’s lack of judgement or carelessness in coming to conclusions. This is simply a description of what we all do in most relationships that we have. Much of our image of others comes from our own spinning, and we take tidbits of information and blend them with our experience to create our delicate tapestries of the world. This is not only natural but necessary: it allows civilization to continue. Think of how slowly we would move through the world if we could only ever proceed from complete information! We would never be able to take in all of the information needed, much less ever get around to making judgements about it.

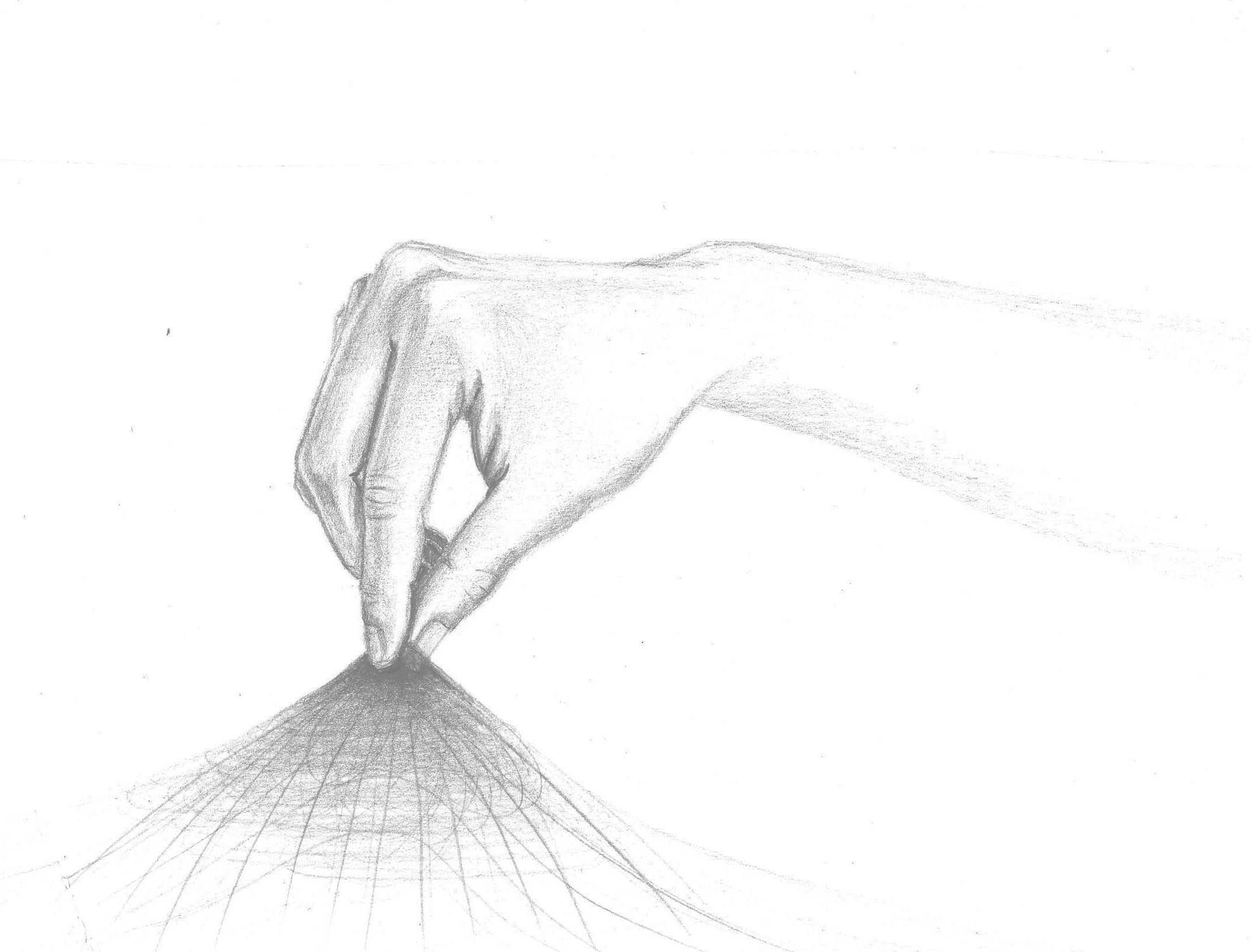

Not only is this an immensely interesting concept for Eliot to be raising, but the image itself is so powerful, and so playful. I imagine Dorothea, perhaps alone in a pensive moment at the beginning of this relationship, with a visible cloud around her of her impressions of Mr. Casaubon, her hopes for their future, her hopes for the person she will become with him–all of these threads spun out of the action of her thoughts, and then from the side comes the hand of the narrator, and in a brief instant the thumb and forefinger of the hand snap together and pinch that cloud of imagination into the size of the few grains of truth from which it was spun. It is sharp, it is vivid, it is vaguely tragic– the passionate contemplation of days, of weeks, reduced down to the size of a pill. And then to pose the rhetorical question, has anyone ever done this? The answer of course is no. Because even if we try to pare down our embellished imaginings to the bare facts, the beauty of our active and creative minds is that we immediately start all over again, seeking out patterns and piecing fragments together to see cohesive wholes.