The first day of Spring is a good time to take a glance back at the receding harshness of the past months, as we say goodbye to our Winter selves and look forward in expectation. What book encapsulates this change better than Tove Jansson’s The True Deceiver? Set in a coastal town in Sweden, this short novel pulls the reader into the claustrophobia of small town life, where the people are hemmed in by the ice, by circumstance, and by the invisible yet ever-present net of social expectations. The question that rises out of this world of neighbourly interdependence and social tension is this: How can you move through the world honestly once you realize that everyone is out for themselves?

The atmosphere created in this book is incredible. It begins in the middle of interminable snow, and the presence of the snow and the ice is felt constantly. The town is set on the shore, and the expanse of ice which stretches out from it is a looming presence at the back of each character’s mind. The yearning for spring, infinitely far off, lingers behind every conversation.

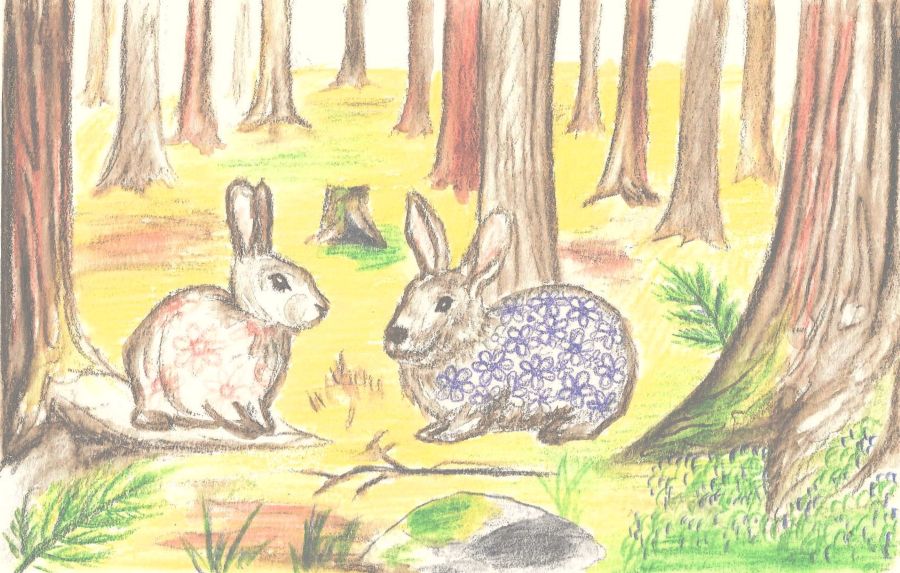

This is especially true for Anna Aemelin, a reclusive woman whose main connection to the world is through painting watercolor illustrations of the forest floor for a picture book series. She can only do this when the snow and ice have melted, and the world is blooming–she paints not from the imagination, but from precise observation, out in the forest. In the winter, she stays entirely in her house, in a dreamy hibernation-like state.

By the end of the book, when spring is approaching and the nights grow shorter, there is an entirely different sense, one of great change and anxiety. How much the characters are at the mercy of time is strongly felt, as well as the depth of the change that occurs with the shifting weather: they really enter a different world, and a different version of themselves emerges. The transformation is turbulent and yet entirely predictable: the stone-solid ice always breaks, and the first seagulls return almost the same night every year.

The strength of the weather is matched by the intensity of Katri Kling. Katri is the only character who seems to feed off the energy of the winter, and she revels in its effect on the village. Yet built into her praise of it, we see perhaps how she clings to it only out of desperation: “Nothing can be as peaceful and endless as a long winter darkness, going on and on, like living in a tunnel where the dark sometimes deepens into night and sometimes eases to twilight, you’re screened from everything, protected, even more alone than usual. You wait and hide like a tree.” She is in her element, but perhaps only because she cannot find a safe place in the world of summertime. We learn that after being orphaned at a young age, she has raised her brother, and she is responsible for them both. Her brother Mats is simple and honest, and has a deep love for boats and boat building.

Katri lives in the mental tunnel of immediate need and responsibility, and perhaps it is easier when the outside world matches that sense of narrowness rather than appearing to be a hospitable landscape of possibilities which she knows are out of her reach. The train of her thoughts illustrates the one-way tunnel of her mind. She thinks about the necessity of getting money, and how getting a large enough quantity could free her from the need for more. With the money, “First of all Mats would get his boat,” and then what might come next is never alluded to. I think that truly her situation is such that she only has this one goal, and throws herself at it, trying to achieve it “wisely and honestly,” and there is room for nothing else. We do not get very many of these direct looks into Katri’s thoughts, and when we do they are intensely focused on achieving this goal, and on scrutinizing her own behavior to match it against her rules. She keeps so much to this confined path that much of her inner life and personality remain a mystery. We know that Anna Amelin is central to her plan to get money, because Anna has money to spare, but we never hear Katri formulate an exact plan: she simply makes herself useful to Anna and becomes part of her inner circle.

Part of the magic and unique feeling of this book is how the narrative voice will occasionally jump into the stream of Katri’s thoughts, and these passages have the feeling of a foreign world. She has a very strict code of conduct that we hear about only in fragmented pieces amid the torrent of her monomaniacal internal monologue. Katri gives herself the third degree after what most people would consider to be a completely normal exchange, demanding, was I being honest? Were my actions motivated by trying to earn points?

“But you never know, you can never really be sure, never completely certain that you haven’t tried to ingratiate yourself in some hateful way — flattery, empty adjectives, the whole sloppy, disgusting machinery that people engage in with impunity all the time everywhere to help them get what they want; maybe an advantage, or not even that, mostly just because it’s the way it’s done, being as agreeable as possible and getting off the hook…”

Since Katri views most instances of social niceties as deception, and will not participate in them, the other villagers look askance at her. As Liljeberg reflects after Katri declines to engage in small talk, “She could easily have remarked on the heavy skiing weather, or asked how he could even see the road, or complained about the town not getting its ploughs out–anything at all to show interest or pretend to show interest, the way people talk to make things a little more pleasant–but no, not Katri Kling.” It is of course funny how he makes a list of possible talking points for her, and also admits that he would be happier with even pretend interest. But grumblings aside, Liljeberg admits that she is honest. In so many other interactions throughout the novel we see people being formally polite while also ignoring each other. As the storekeeper makes empty small talk, “Mats nodded without listening and drank his Coca-Cola at the counter, slowly.” Similarly, “Fru Sundblom didn’t seem to be listening. She looked grimly out the window, said the usual things about the snow, then very soon went home.” Evidently one can satisfactorily follow the social rules with empty gestures, and no one will complain directly about it. In a truly iconic scene, Anna realizes that she has never liked coffee, and it had never occurred to her to have an opinion about it. As a guest, the social script says to accept it when offered, and as a hostess the script says to offer it. When Katri as her guest declines coffee, Anna for the first time understands that there is even another option. There are parts of the characters’ inner selves which are hidden from them, not necessarily actively suppressed but simply never looked into because all their focus is on playing their part in society well.

Anna appreciates that Katri is different.

When Katri came to the rabbit house, she put down her bag in the hall and announced that she couldn’t stay. “Don’t you have the time? Not even a little while?” “Yes, I do have time. But I can’t stay.” “Miss Kling, wouldn’t you like to stay?” “No, “ Katri answered. Then Anna smiled, and without a trace of her usual confusion, she said, “Do you know, Miss Kling, you’re a very unusual person. I’ve never met anyone so terribly — and I use the word in the sense of frightening — so terribly honest. I want you to listen, now, because I think what I have to say is important. You’re young, and perhaps you don’t yet know so much about life, but believe me, almost everyone tries to play a part, to be what they’re not.” Anna thought for a moment. “Not Madame Nygard, but that’s another matter… You know, I notice much more than people realise. Don’t misunderstand me — of course they mean well. I’ve met nothing but kindness my whole life. Nevertheless… you, Miss Kling, are always yourself, and that feels somehow…”, she hesitated, “…different. I trust you.” Katri looked at Anna, who, entirely in passing, in friendly earnest, had given the go-ahead for an authorised conquest of the rabbit house. Anna continued. “Now don’t take this the wrong way, Miss Kling, but I find your way of never saying what a person expects you to say, I find it somehow appealing. In you there’s no, if you’ll pardon my saying so, no trace of what people call politeness… And politeness can sometimes be almost a kind of deceit, can it not? Do you know what I mean?” “Yes,” said Katri. “I do.”

Anna is right to identify Katri’s lack of politeness. But in what sense is Katri being “always herself?” Katri’s way of being is not a default, it is carefully constructed and self-censoring. She is constantly questioning her behavior, drawing boundaries, using self control to act the way she does. She tries to be perfectly consistent, which Anna picks up on, and so she is predictable in that sense. But Anna thinks that Katri might not know that people play a part. She doesn’t know that Katri thinks of this constantly and is deliberately making rules for herself about it. We know from glimpses into her thoughts that Katri is “playing a part” but in her own rules, trying to get something, and presenting a certain face on purpose.

In what form can politeness coincide with being “always yourself?” Madame Nygård seems to be a possible glimmer of this, as Anna mentions. She acts the formal role of the hostess, offering the best chair to visitors, but she also cultivates a real spirit of warmth. One of the few details we get about her home is that while everyone was swept away by a societal fad and got rid of their “big stoves” in favor of more modern options, Madame Nygård did not. She seems to embody the predictability and stability that Katri values, and she is not ruled by the will of the masses. Rather than indicating obstinacy, I think this paints her as someone who is rooted in what is positive and genuine in social customs rather than what is arbitrary. Madame Nygård really only appears a few times in the story, yet she ends up serving as an important contrast to Katri, and provides perhaps an alternate path to follow for someone who is disenchanted by the artificiality or shallowness of the rules of politeness.

In an exchange late in the book, Anna is lamenting the fact that she now speaks ill of people when she never used to. “Believe me, I never did…But why? Did I trust everyone? Or was it only that I forgave them?” “Well, well,” said Madame Nygård. “That snow fell a long time ago, did it not?” “But you trust people, don’t you?” “Yes, I suppose I do. Why shouldn’t I? One sees and hears a great deal about the way people behave, but that’s their problem. One doesn’t want to make things worse by not believing that they mean what they say.”

I think that is important about this exchange is that Madame Nygård is observant–she is not blind to the reality of how people act–but those observations are not setting her against them. Being distrustful or guarded against people is not perhaps the only, or the most logical, response when you realize that they have ulterior motives. If one does make that change, they might be ‘making things worse,’ creating the society they fear by drawing away and contributing to a negative cycle of mistrust and deception.

Madame Nygård is also characterized by a lack of hurry, and a sense of quiet and peacefulness–she is observing and listening instead of filling every moment with small talk or niceties. This contrasts her with many other villagers. So many of the socially acceptable modes of acting in the book are people just filling up space with empty phrases, and then getting called friendly and normal. While those instances point to shallowness, Madame Nygård’s silences provide real space for engagement, for her to be close to and understand people. But she also has a firmness about her, a straightforward manner. It seems that when she does engage in “politeness” she is doing it very intentionally, not as a matter of habit or compulsion. And by focusing her attention on others, we do get the sense that her words and actions are “for” them and not for bolstering her own image or for saving up for later favors.

The book ends with a blossoming, as magical and surreal as the beginning, and leaves us wanting more. Anna and Katri have emerged as different people, and we barely get to meet their new selves. At the cracking of the ice they step off of the pages, and we can no longer trace their footsteps in the snow. Luckily we still have this small magic mirror into a season of their lives, and there is enough in it to reflect on to last until the cold returns–and beyond!